What to know about Google's plans for wetlands in Fort Wayne

“When you just take a quarter acre here and a quarter acre there, over and over again, it adds up. So to me, you have to resist that loss. Every single time somebody wants to do it.” -Bruce Kingsbury, Director of Purdue Fort Wayne’s Environmental Resources Center (ERC) and Professor of Biology.

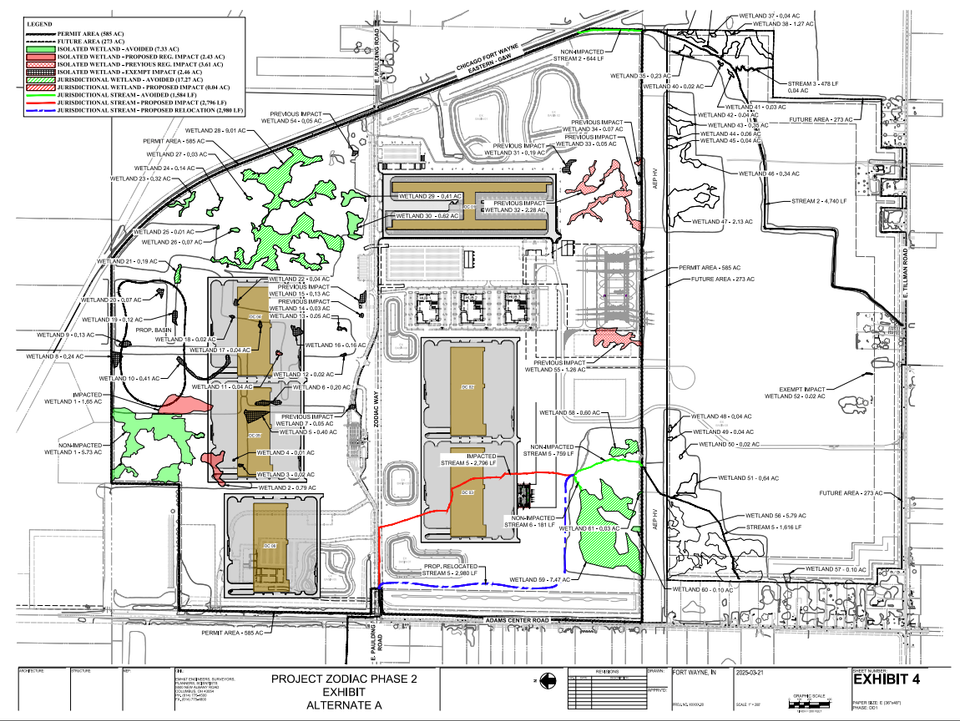

Google is entering Phase 2 of its massive data center buildout in Southeast Allen County. This is bringing up some concerns about its impact on local water systems, specifically wetlands.

- Last week, Google sought approval from the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) to build on about 2.47 acres of wetlands, including some that are protected in the state of Indiana.

- Quick note: you have until Sept. 11 to submit comments about Google’s proposal to IDEM’s Project Manager Evan White at EVWhite@IDEM.IN.Gov or 317-671-6698. With enough comments, IDEM might host a public hearing.

So what’s the big picture of Google’s ask, and how might it affect the local environment and your water bill?

We contacted IDEM for more information, and they said they’re not taking interviews on the topic, but: “Wetland determinations are made in accordance with Indiana’s State Regulated Wetland Law…. If any potential permitting discrepancies are raised during the public comment period, IDEM will thoroughly evaluate and address them before making a final decision.”

Let’s start with a little context:

- Since Google revealed itself to be the company behind “Project Zodiac,” its investment in Fort Wayne has more than doubled, likely driven by the global AI arms race. Google first announced it was planning to invest “at least $845 million” in Fort Wayne’s data center campus, but that figure grew to “at least $2 billion” by the time the data center broke ground in April 2024. Inside Indiana Business reports that Google plans to use its Fort Wayne data center to power AI innovations and grow its Google Cloud business.

- According to Google’s recent public notice, this “extra buildout” in Phase 2 is what caused the expansion into wetlands in Southeast Allen County. Representatives with the project noted that they are avoiding some pockets of wetland, but “can’t build around two specific sections,” totaling about 2.47 acres – about .04 acres of which is protected or “jurisdictional” under the Clean Water Act.

- Google already plans to fill in more than six acres of wetlands for the six buildings of Phases 1 and 2. Combined with the new projected losses (2.47 acres), the amount would reach 8.54 acres – not counting future phases of the campus buildout, which is expected to total 12 buildings.

- Because some of these wetlands are protected, Google is required to seek permission and make up for wetland losses – but not in the same part of Allen County (Southeast) where they’re filling wetlands. According to Inside Indiana Business, “Google is proposing to purchase wetlands mitigation credits in Eel River Township on the northwestern edge of Allen County.” Credits allow companies to offset wetland destruction by creating or enhancing wetlands in another part of the state.

What are the potential impacts?

We consulted the Director of Purdue Fort Wayne’s Environmental Resources Center (ERC) and Professor of Biology Bruce Kingsbury for insight on Fort Wayne’s wetlands and their value.

Here are a few quick things to know:

- Wetlands have many functional benefits for their immediate communities. Along with natural beauty and providing vital habitats for wildlife, they also store and detain water to mitigate flooding and naturally filter water before it continues through the water system. “If you erase the wetlands on the landscape, you’re basically removing all these tubs that can hold water and then gradually release it,” Kingsbury says. Filling wetlands contributes to increased flooding and more water processing, often resulting in higher costs for residential water users.

- Supporting or protecting wetlands in another place doesn’t change the damage done to the community where wetlands are filled. Kingsbury points out that wetland mitigation credits technically satisfy the current policy on wetland preservation (No Net Loss). But “it doesn’t make up for” the effects on those downstream, who are likely to see increased flooding as a result of lost wetlands.

- Smaller, isolated wetlands are not protected in the U.S. or Indiana, yet they play an important – outsized – role in preserving wildlife here. Kingsbury says: “What we find is almost all of the amphibians and reptiles in peril in the Midwest and in Indiana are reliant on ephemeral wetlands. These are little, seasonal wetlands that don’t look like anything in the fall, but in the spring, they fill with water and hold water long enough for species, like migrating birds and dragonflies, to use them to be successful. Then they dry up.” Because these wetlands are not protected federally, it leaves them to the states, and as Kingsbury says: “Indiana has selected to reduce protection of isolated wetlands repeatedly over the past five years.”

So where does all of this leave us?

- Ultimately, though some wetlands are not technically classified as “protected,” Kingsbury says they still serve vital functions, and losing small plots here and there adds up to bigger costs. Kingsbury refers to this as the cumulative effect of wetland removal. “Back in the day, a notable attribute of Indiana was the amount of wetlands we had – millions of acres – and almost all of that is gone. When you just take a quarter acre here and a quarter acre there, over and over again, it adds up. So to me, you have to resist that loss. Every single time somebody wants to do it.”

- There are still a lot of unknowns about data centers’ water use, in general, making it difficult to assess the value of data centers compared to their total environmental costs. Not counting wetlands, large data centers consume up to five million gallons of water per day – about the same as a small town of 10,000-50,000 people – to cool their supercomputers, placing significant strain on existing water systems. But as the Chicago Sun-Times reports: “secrecy agreements between government bodies and companies” are keeping information about water usage from being publicly disclosed.

- All of this is adding up to higher water (and energy) bills for residents in data-center-heavy states across the U.S.– and Indiana could be next. The number of data centers in Indiana is "booming" – with Gov. Mike Braun telling WTHR Indianapolis the state has "an opportunity to become a national leader in this growing industry." Indiana currently has more than 70 facilities, up about 30% from March alone. And residents are pushing back, but to little avail.

- Data centers are getting significant incentives from cities, too. Despite being a wealthy global tech giant, Google’s data center has received financial benefits from the City of Fort Wayne taxpayers, including a 10-year, 50% tax abatement. In return, officials told Greater Fort Wayne Business Weekly, it’s expected to bring a "steep rise in property tax income" to Southeast Fort Wayne. (See our previous report for additional considerations, including carbon impacts and local jobs.)

Ultimately, it’s going to take policy change – perhaps both in how wetlands are designated and protected in Indiana, as well as how much information data centers must share with the public about their contracts with government entities.

As Little River Wetlands Project tells us:

“Data centers, in particular, require enormous amounts of water for cooling, placing additional strain on local water supplies. This raises important questions about how we balance development with long-term community resilience.

Organizations like Little River Wetlands Project are working every day to restore and protect wetlands in our region. These living systems filter pollutants, replenish aquifers, and act as a first line of defense against flooding. Protecting them is not only about conservation—it is about protecting the people, communities, and future generations who depend on them.

We invite all Hoosiers to join us in this effort. Learn more about the value of wetlands, support local conservation groups, and speak up for stronger protections. Together, we can ensure that clean water and resilient landscapes remain part of Indiana’s legacy.”

Quick reminder: You can send comments to IDEM (EVWhite@IDEM.IN.Gov) regarding Google’s wetland plans in Fort Wayne now through Sept. 11.

Thanks for reading and considering all of this, Locals.

Kara Hackett